| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 10 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Tom Hibbard and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-rolfe-rb-hibbard.shtml

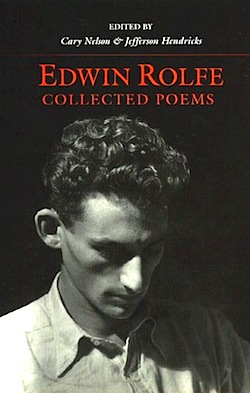

«Collected Poems of Edwin Rolfe», Cary Nelson and Jefferson Hendricks, Eds.,

reviewed by

Tom Hibbard

University of Illinois Press 1993 Urbana/Chicago 337pp.

… they were young, there was much they did not know

— Genevieve Taggard

^

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred in the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

^

This is the opening paragraph of Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell To Arms, published in 1929. Of course, the love-and-war experiences on which the book is based took place about a decade earlier in World War I, (1914–1918). Hemingway’s novel, though about political events, is not political. Malcolm Cowley points out early in Exile’s Return “of political conviction [Hemingway’s hero] had hardly a trace… .” Cowley goes on to indicate that this early 20th Century hero not only lacked political conviction but was revolted by it. He quotes from the novel:

^

I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice and the expression in vain. We had heard them, sometimes standing in the rain almost out of earshot… and had read them on proclamations… now for a long time, and I had seen nothing sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the stockyards at Chicago if nothing was done with the meat except to bury it… .Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.

^

Deep inside some sort of political feelings must have stirred Hemingway to go to Europe and join the ambulance corps during wartime. Moreover, other American writers also were drawn to the tumult in Europe. Cowley was a driver in the war, as were Dos Passos, Julien Green, E.E. Cummings, Slater Brown, Louis Bromfield, Dashiell Hammett and others. If Hemingway was apolitical perhaps it was because Europe and the United States were saturated with a superficial sort of political bickering. The Russian Revolution in 1917 created an atmosphere of revolution and radicalism. Like Hemingway, other Modernists were not aligned strictly politically. Ezra Pound’s loss of personal friends in World War I pushed him toward pacificism. Perhaps American expatriates were able to view the political activities of countries on a foreign continent as currents in the immense vortex of world-wide transformation. The Modernists, including and perhaps especially Irishman James Joyce, were bent on radical aesthetic ideas. Pound’s Cantos are Cubist precursors of all forms of abstract and multi-media creations, economic and ecological models and diagrammatic representations as are some forms of today’s visual poetry. Like science, Modernist art and writing hoped to plummet the ineffable depths of matter and creation before the viewers’ eyes in the laboratories of canvas, sculpture and text. Paris in the twenties was not about politics but the problems of existence in a disembodied world.

^

In the U.S., politics was more the milieu of ideas. Due to lingering economic issues from the excesses of the Gilded Age, the rise of labor, immigration, racial injustice, the challenges that the early 20th-century wave of Communism posed for Democracy; a phalanx of Leftist writers pressed for the recognition of new perspectives toward the poor, the working classes, women and society in general. It wasn’t long after returning from Paris that Malcolm Cowley found his literary magazine “Broom” suppressed in New York by the U.S. Post Office (1923). There were many radicals in the U.S. who did not share Hemingway’s scruples about being political. There was a thirst for anarchy and revolution. Activist journalist Mike Gold had already published “Toward a Proletarian Art” in “The Liberator,” which he edited, in 1921. Kenneth Fearing published many poems in the twenties in “The New Masses.” When the stock market crashed in 1929, beginning the decade of the Great Depression, the flood gates were officially opened for politically influenced poetry collections, plays, films, novels (such as Robert Cantwell’s Land of Plenty, 1934; Horace McCoy’s They Shoot Horses Don’t They, 1935; Jack Conroy’s The Disinherited and James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, 1934) irrigating the great land of Roosevelt’s New Deal.

^

Due to its close ties to the Progressive Party, the University of Wisconsin in Madison began an Experimental College during the thirties. Though it didn’t last the decade, it attracted some well-known radical writers, including Fearing, Carl Rakosi, Kenneth Patchen and James T. Farrell, author of the Studs Lonigan trilogy. The Experimental College in particular like radicalism in general was tied to specific changes for society, such as unemployment compensation, direct primaries, trust busting, taxing railroads, many of these ideas being considered commonplace today. So why would these writers, these off-kilter foot-soldiers of misplaced harvests and these tramp philosophers of genial Sunday-afternoon roof-tops and bloody adventurers of bare-knuckle boxing matches hold interest to readers today? The economic parallels are perhaps incidental. Marcus Klein writes in an essay titled ‘The Roots of Radicals’

^

The class struggle carried conditions of immediacy and of direct and exact references — and for that reason there can be little doubt, the proletarian movement was exciting, even to that majority of writers who shared in no ideology.

^

In troubled economic times, need wears through. The deprivation of the Thirties brought with it a liberating disorientation, a piercing longing for and envisioning of “imaginative reality” and even a “critical reality” above “natural reality.” “Proletarian writing,” as it was somewhat euphemistically termed, became realism, a more intense realism, a grimmer perception of the uneven textures and overlooked contours of life due to unabated highs and lows. The way that political radicalism of the thirties and forties comes to us today is as a synonym for imagination, poetry, newness, even integrity and honesty.

^

One of the writers that exemplifies this — and there are many — is Edwin Rolfe. Rolfe was born Solomon Fishman in Philadelphia in 1909, the son of Jewish Russian immigrants. The family moved to New York, where the father became a union official, a socialist and later joined a faction of the Communist party. Rolfe got his name from publications in which he used the pen name Edwin Rolfe. One of his early poems was “To a Subway Worker” published in the “Daily Worker.“ In 1929, Rolfe left New York and enrolled in the Experimental College at University of Wisconsin. He ran out of money after a year and a half and returned to New York.

^

His first collection of poems, To My Contemporaries, was published in 1936, the same year he was married. There is no question that early in his career Rolfe was Communist, yet it is equally true that he, like so many others, was frequently at odds with the party, often dropped out of it, finding it restrictive and pedagogic. Later in 1936, Spanish army officers, supported by fascist groups (and some U.S. corporations), rebelled against the elected Communist government of Spain, and the Spanish Civil War was underway. Regarded as a preliminary to World War II and a testing ground for Nazi military strength, the Spanish Civil War attracted volunteers, including several well-known writers, from many countries to fight in the International Brigades, especially the Lincoln and Washington battalions from the United States. In the spring of 1937, Rolfe was off to join up, at first as editor of the Volunteer For Liberty, an English-language magazine in Madrid, and the following year as a member of the Lincoln Battalion. After the war, in 1939, along with his wife in Barcelona, Rolfe returned to the United States. Nazi-supported fascist Franco had taken over Spain’s government. (Anyway, in fighting fascism there is always a modicum of victory in losing.)

^

Rolfe met Hemingway in Spain, and the two began a life-long correspondence. Hemingway wrote For Whom The Bell Tolls about the Spanish Civil War, which was published in 1940. Hemingway also contributed to making a movie about the war, titled Spanish Earth. Rolfe, for his part, was commissioned by Random House to write a history of the Lincoln Battalion, which was published in 1939. In 1943 he was drafted and sent to basic training at Camp Wolters in Texas. The two writers must have turned exhaustively their thoughts about what had taken place, Hemingway remembering Spain from the early years as a carefree expatriate and Rolfe, a young writer-recruit, getting his initial taste of both combat and Spain. Though Rolfe was barred from being a U.S. army officer for having fought in Spain, the years of World War II were not characterized by inflamed anti-Communism. Later in the decade of the forties, the House Un-American Activities Committee, which had focused on German pro-Nazism during the war, became a standing committee to investigate Communist spying and “subversion of the U.S. Constitution.” It was at this time that Rolfe shaped, reshaped and expanded the slight number of poems he had written during the war in Spain. And Hemingway never wavered in his support of Rolfe and the Lincoln volunteers, whom he vigilantly regarded as fighters against fascism (Hemingway’s term was “premature anti-fascist.”)

^

In the case of Rolfe, Hemingway seems to be precisely correct. In the broadest sense, Rolfe was essentially and primarily a fighter against fascism. It is the fermenting, like wine in a mountain wineskin, of the poems in Rolfe’s Spanish War collection, First Love, that makes it the exceptional collection that it is. Rolfe has taken his post-war experiences and worked them into his recounting of the war, creating a metaphor of deep-seated brutality, antagonism, illusion and effects of non-being. The writing is descriptive, painstakingly comprehensive, so that it cannot collapse into its own antipode. It is as much about the landscape of intimidation and McCarthyism as it is about the landscape of Spain. Each of the thirty-nine poems covering sixty-two pages (in Collected Poems) blocks out a different area of insensitivity, warns against a different form of trickery and betrayal, exposes an aspect of tyranny, attempts to maintain ties between human beings that are breaking apart and drifting toward a society of enemies.

^

As is also generally the case with Kenneth Fearing’s poetry, Rolfe’s First Love is truthful beyond politics. It is a complex association of fact and idea, the particular and general, loyalty and adventure, commitment and detachment, work and idealism, empiricism and conceptualizing. Writes Rolfe editor Carey Nelson, “[Rolfe’s poetry] insists that the intense subjectivity of romantic love and the daunting generality of social struggle are connected.” And again: “[Rolfe’s poetry suggests] that the two discursive registers — lyricism and polemicism — are interdependent.” Above all, the lucidness of its portrayal cannot be missed. It is based on ecstatic experience rather than fitted to well-defined political aims.

^

The reason for opening this piece of criticism with a quote from Hemingway is that it seems that radical politics, particularly of the thirties, begins in a sentimental tactile knowledge of worlds that appear to be transient, that are in some way all worlds and that to exist mainly in the realm of the imagination. To know a world is to care about it. To fight in a war is to live in the future. The evidence of this in First Love is prominent at the start. The collection’s opening poem, “Entry,” begins with the lines:

^

Running from the shadow-coach

silent on the darkling plain,

we whispered: be careful.

Recalled the always-dimmed headlights, the full halt,

the silence, the unspoken word.

All yesterdays blurred

while scouts advanced a mile,

returned, reported: All’s well.

And in the deep dusk we relaxed, whispered,

thinking: now, now the beginning;

hastily passed the loaves of bread around,

tinned sardines, Gauloises, chocolate, cheese,

stuffed them in pockets; filled a few canteens

with wine; drew the stiff curtains down

and, choking, smoked — all fifty of us —

a final cigarette.

Then, two at a time, leaped the wide ditch,

ran cross-meadow, carefully climbed

the flank of a sharp ridge,

knowing already

what the word enemy means.

^

In “Prophecy in Stone,” Rolfe again considers what the setting reveals.

^

Ferret out

a race’s history in a finger’s curve,

see sun-washed walls flaking to dust,

the dust to powder won by the wind;

deep gashes, rust of rain and sun,

stones fallen, and the black deep grooves

^

Later in the poem, Rolfe mentions a “barbed enclosure,” “nails jut from walls,” all of which is “evidence/ of grandeur ground to death.” In “More Than Flesh to Fathom” are the lines

^

Upon the speckled wall there grew

flowers I could not pluck and grass

stabbing to touch and limitless

landscape I could not penetrate.

Only the sobbing brook, the muddy

flow of the turgent stream I knew,

and blindly clutching a twig…

^

In “Elegia,” a long penultimate poem written in 1947, following a return to Spain ten years after Rolfe left it, the sensual memories have aged into the eloquent words of a “lover, husband, son.”

^

Madrid Madrid Madrid Madrid

I call your name endlessly, savor it like a lover.

Ten irretrievable years have exploded like bombs

since last I saw you, since last I slept

in your arms of tenderness and wounded granite.

Ten years since I touched your face in the sun,

ten years since the homeless Guadarrama winds

moaned like shivering orphans through your veins

and I moaned with them

^

In another strophe:

^

Madrid, in these days of our planet’s anguish,

forged by the men whose mock morality

begins and ends with the tape of the stock exchanges,

I too sometimes despair. I weep with your dead young poet.

Like him I curse our age and cite the endless wars,

the exiles, dangers, fears, our weariness

of blood, and blind survival, when so many

homes, wives, even memories, are lost.

^

Rolfe’s experiences in Spain parallel the experiences that many writers including a writer like John Steinbeck took from the Great Depression. Some of the poetry could as easily be about the thirties or the fifties. Rolfe writes in “Elegia” that he is “wandering, bitter, in this bitter age.” The poem “Soledad” begins, “Nothing respects your solitude.” He compares dreams to “wounds and mutilation in battle,” meaning that they too are irrelevant, so much litter. In recalling “the flesh cut open, the gangrened limbs, the rot,” he is talking about the several worlds in which he has lived as it is and was reflected in war scenes. He claims, “We were right: how right we never discovered.” The line, “The city weeps. The city wakens, weeping” could for Rolfe be about New York, Madrid or Los Angeles. In a notebook, Rolfe tells himself to write “as though you lived in an occupied country.”

^

In my view, the lines that portray Rolfe most clearly as a radical poet rather than a committed Communist in this collection are these last lines from “Marching Song of the Children of Darkness.”

^

yes, all of us are guerrillas: each, as his life unfolds,

must fight man’s inhumanity — the monstrous synthesis

arrayed against him, in chaos, in malice, in this

most cruelly impossible of all possible worlds.

^

The title poem, “First Love,” was written four years after Rolfe left Spain when he was in basic training in Texas. Rolfe became ill and was excused from duty. The poem begins with the lines, “Again I am summoned to the eternal field/ green with the blood still fresh at the roots of flowers.” Later lines are

^

But why are my thoughts in another country?

Why do I always return to the sunken road through corroded hills,

with the Moorish castle’s shadow casting ruins over my shoulder

and the black-smocked girl approaching, her hands laden with grapes?

^

The idea of first love is first and last love, a love that cannot be superseded, an understanding, emanating from the quirkiness of life, that is used as a measuring stick. Rolfe is saying that in his experiences in Spain he was able to get outside the restraints of custom and the insensitivity of stagnant society in general, to see beneath the surface, to feel in a way he did not feel before and in a way that he will never forget. First love is radicalism or activism itself, a more-than-conforming commitment, abstract ideas that are felt. He was able to think, to envision himself in the context of what was taking place and to renew his sense of himself as an important part of humanity as a whole. The basis of Rolfe”s First Love is that perception itself is radical, that poetry must find its basis in this sort of perception.

^

One of the best of the thirties writers, Jack Conroy, writes:

^

Certainly, the emphasis on social concerns gave a heft and significance to their works often lacking in current fiction. The better writers of the thirties did have a social message to convey, and some of them did express it vividly and significantly.

^

The political ideas enter in and are important, but (as perhaps Hemingway demonstrates) they are so all-encompassing, made more so I would guess by the opacities of war, and at the same time so clearly limited to a strictly human type of endeavor that they can be expressed only in an intense, fragmented, striking, wide-ranging, hypothetical language that reaches toward the only-partially-known.

^

In dire times, American radical writers of the Depression turned to writing news-stand fiction. Kenneth Fearing for a while was a rich man when his 1946 mystery novel The Big Clock was made into a movie by Paramount several years later. Fearing received well over a quarter of a million dollars for the movie rights in current value (though he and his wife at the time quickly drank it all up, and Fearing died broke). Rolfe too tried his hand at the genre. Things looked bright for the Rolfes when Hollywood became interested in his co-written 1948 Bantam paperback Murder In The Glass Room and was ready to purchase the movie rights. However, in 1947 HUAC had begun conducting its well-known investigation of Communism in the film industry, and, though he was not one of the notorious “Hollywood 10,” Rolfe was essentially blacklisted in the industry. The movie was not produced, and Rolfe’s script work disappeared.

^

It would seem that Rolfe’s blacklisting had at least one good effect. First Love, still today a little known work, was published in 1951. By accounts it was published by Larry Edmunds Book Shop in Los Angeles, and it was self-published by Rolfe. The collection, clearly highly reworked by Rolfe during the forties and perhaps early fifties and undoubtedly much influenced by the treacherous and high-voltage atmosphere created by the HUAC probe, would not have been what it is and might not have been finished at all if Rolfe had become a successful Hollywood script writer. Nor, perhaps, would Rolfe’s poems directly about the red-baiting McCarthy 1950s, published in 1955, a collection titled Permit Me Refuge (somewhat gratingly similar to James Agee’s Permit Me Voyage put together much earlier in the thirties), along with many uncollected poems of the same time, have been written.* Rolfe died in 1954 at age 45 of a heart attack (Agee died one year later also of a heart attack). It seems that what we want to say about Rolfe — and with him the radical writers of the Great Depression — is that he was an excellent poet, an inspiring person, an admirable person, with a hard-fought and abiding commitment to the future of mankind. Perhaps Langston Hughes’ poem written during the Spanish Civil War for Rolfe on his birthday while Hughes was a correspondent in Madrid might serve as an epitaph.

^

Poet

On the battle front of the world,

What does your heart hear,

What poems unfurl

Their flags made of blood

To flame in our sky —

Bright banners

Made of words

With red wings to fly

Over the trenches,

And over frontiers,

And over all barriers of time

Through the years

To sing this story

Of Spain

On the ramparts of the world —

What does your heart hear,

Poet,

What songs unfurl?

* In the interest of fairness, accurate perspective, I feel moved to include the information that Rolfe’s blacklisting in Hollywood was not his first encounter with this sort of treatment. In 1934, Rolfe was fired from the Daily Worker because a fellow writer, a “comrad” deliberately lied about him. Editor Nelson talks about the incident in the introduction and notes that the poem “Definition,” in which the words “charlatan” and “false” are used to describe his accuser, was Rolfe’s response.

Tom Hibbard has had several bio notes appear in Jacket. A fairly long one in particular is attached to his Jacques Derrida review and/ or long poem “Big Snow” in Jacket 37 (along with a photo). Since then reviews of Michael Rothenberg and William Allegrezza have appeared in issues 12 and 13 of Eileen Tabios’ Galatea Resurrects, and a review of Mark Young’s selected poems Pelican Dreaming appears in issue 14 of Big Bridge. Several new poems are online at Moria winter-spring 2009 and the final issue of Jack. Also Andy Gricivic’s Cannot Exist. Hibbard read his poetry at Myopic Books in Chicago in November of 2009. Most of these poems are from his unfinished collection The Sacred River of Consciousness.