| Jacket 39 — Early 2010 | Jacket 39 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 20 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Bob Arnold and Kent Johnson and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/39/iv-arnold-ivb-johnson.shtml

JACKET

INTERVIEW

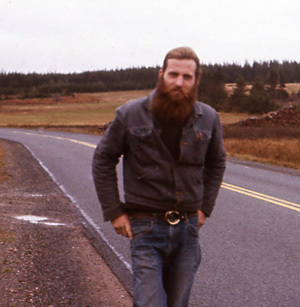

Bob Arnold, 2007, in Carson’s music store. Photo Susan Arnold.

Bob Arnold in conversation with

Kent Johnson

10 March 2010

Bob Arnold was born and raised in the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts. While employed as a stone builder and landscaper, his books of poetry have appeared since 1974. He is the editor and publisher of Longhouse. For many years he has made a home in Vermont with his wife Susan and their son Carson. “Bob Arnold builds stone walls. He also builds poems that will last for generations and as natural as stones working together. Edwin Muir once remarked that modern poetry is not read by ‘the people,’ because it no longer tells a story. ‘The people’ should reconsider…”

Oyster Boy Review 13 (Summer 2001)

Also see “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Vermont Poet: ” Bob Arnold in conversation with Gerald Hausman, 2007, in Jacket 34.

1

Kent Johnson: Bob, it’s safe to say that very few poets in the U.S. have had the kind of “career” you have had. In addition to being a poet, non-fiction writer, and maestro of the epistolary form (the selected letters are surely coming!), you are a master stonemason, a builder, and a first-class expert on chainsaws and their ways. An all around, grimy handed handyman, one might say. You’ve built your own multi-structure homestead in the mountains of Vermont, where you’ve lived, now, for decades. And in your spare time (if it’s right to call such your “spare time”), you’ve run, in collaboration with your companion Susan, Longhouse Publishers — one of the longest-running, most active fine presses in the country. To start, could you talk a little about this life, how it came to be, and how the daily work you do “for a living” combines with the daily work you do for poetry?

2

Bob Arnold: Going to the last part of your question first, Kent — I have very little to write about until I’m out in life living it. This means with the chainsaws, the hammers, the stonework, the woods, the fields, the river, and with the girl, Susan. It’s been that way for almost 40 years and I’m doing everything within my powers to make sure it doesn’t stop. Even if a lot of the time it seems fueled on a dream, gritty determination and the greatest thing that ever hit town, team-work. I can’t say enough for love and marriage. And I know that thought is going to make some smile, and make others grimace.

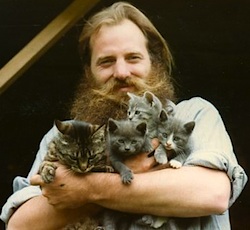

Bob Arnold in Newfoundland, 1975, photo Susan Arnold

3

How it all came about? Honestly, it beats me. I want to know and I don’t want to know. I trust trust, and I’ve been visited repeatedly by bad luck slipping and sliding its way to some good luck. You’d be surprised how often it happens, and no matter how often it happens, I sometimes think it won’t ever happen again. And then it does. My friend Franco Beltrametti once said, “Chance is like an intersecting angel.” He said this near the end of his too short life. I think the key is staying loose, eyes open, available and even vulnerable, open for a pass. It’s downright athletic. After a life of cutting trees, roofing homes, huts and barns, cribbing up old shacks and cabins and houses, painting and painting, raking and raking, wood-splitting & wood-splitting, the body and the mind get to know one another. If you develop the mind along with the body, it could become a lantern burning bright.

4

Of course I must tip my cap to my background — a flinty Irish mother from Belfast with a large family of storytellers and hard workers, lots of kids. And on my father’s side, all lumbermen, mainly businessmen when I was born, but all the forefathers were choppers, sawyers, drivers, mountain butchers. The businessmen wanted the oldest son, me, to learn the ropes, so I was dropped into the lumberyards at age ten and worked every day after school with more Irishman and Poles and all through each summer — first unloading boxcars of western and eastern lumber and loading truck deliveries, and then when I was a little older, receiving those truck deliveries on some muddy hillside with a carpentry crew and two or three spec houses going up. The plan was to teach me the business and then after college go into the business. Put on a tie. Instead, the sixties got in the way, with its music and rebellion and tribal strength, and I barely got out of high school.

Bob Arnold drawing water for his cabin, 1975 photo Susan Arnold

5

Forget college, I was drafted into the Vietnam War, and as a member through high school with the War Resisters League, I continued my protest and earned a conscientious objector status which put me in Vermont, only a few clicks from my birthplace of western Massachusetts. I fell in love with a girl, who then fell out of love with me, or at least my move to the woods — a cabin built by a river; the boy/monk with the long beard who walked to town ten miles away or caught rides, however, for two years with sympathetic souls — sometimes a farmer, sometimes a businessman. It takes all kinds. The time period was now just leaving the aura of the sixties, and while I had long hair and beard and dressed in clean hand-me-downs, I took no part in drugs, smoking, drinking or partying. I read books, thousands of books. And cut wood. And built my place. And piled stone. And wrote poems back to it all, as if a grace. And learned my trade.

6

KJ: No drugs or drinking. Now there’s something exemplary and instructional for younger poets! I’m trying to think of examples within this “tradition” — I mean poets who have chosen forms of living, if that’s the phrase, far outside the typical social and institutional spaces that one tends to associate with a literary career, especially now, in our times and climes.

7

Your fellow New Englander Dickinson would be, of course, the archetypal example, and no one’s likely to match the constancy of her eschewal of self-promotion. Lorine Niedecker, or William Bronk, to some extent, might be later cases… Spicer, I guess, as an urban example, though that’s more complicated. There are poets who have tried, and often to successful effect, to strike the pose of the “outsider,” like Frost, say, or those who, thanks to fortunate inheritance, have been able to afford an attitude of nonchalance or scorn towards mere literary business, and so forth: James Merrill, Fredrick Seidel, or Michael Palmer, to some extent, for recent examples. But that’s exactly what I don’t mean (without meaning any slight towards those brilliant writers at all)… I suppose those who choose the hardscrabble, idiosyncratic path I’m thinking of means, precisely, that their names will be less likely to roll off the tongue when people get to making lists.

8

I realize this is all slippery territory and definitions get troublesome, but anyway: Who else? Help me out. Among poets who have devoted themselves, like you, to fine press publishing, who have given so much of their energies to others, there must be a few unassuming folks with “modest, local address” you’d want to mention.

9

BA: You know, Kent, long ago and not too faraway I once came to a small Vermont town on-foot. And I say on-foot because I hiked a good deal of the way to get to this town and then managed by hitching a few rides the closer I got to the town as the roads widened and were more traveled. And in this town, which was a ski-town with fancy shops and some boutiques, there was a hidden away shop, completely different looking than anything else in the town, with its dull painted clapboards but wide and white painted picture windows, and the glory that was behind those windows!

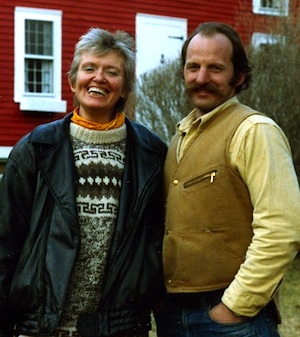

Bob Arnold and new spring kittens, 1984 photo Susan Arnold

10

Inside the shop were two spacious rooms and in the first was filled as if packed and managed by elves with deep and damp smelling herbs, rows and stations and floor to ceiling built cases of glass bottles and tins and jugs and bags filled with medicinal potions. Everywhere you looked! It caught all your clothing instantaneously and overwhelmed your senses. The store was run by a bird-like woman, a heron on tall legs with precise hearing and vision with long gray hair piled up into a bun on her head. I never saw her smile and she came into the store from a corner stairway which came down from the upstairs where she lived. I saw all of this in about the first minute. Maybe because I caught the woman and the store hour at just the right time of encapsulating a complete life of earth medicines and good health and exotic visions because the herbs and all belongings in the two room store came from all around the world. When I moved carefully through the first room and rounded a corner to the second room it was filled just as magnanimously as the herb room, but this room was all of books. Books like a dreamland because they ranged from every size and subject and seemed arranged more by color than subject.

11

I’d spend the next five years of my life visiting this room with all-day sessions and always getting to this room, even though the store had two doors, by way of the herbs. It would be a tradition. And of course all the books reeked of the herbs or some melodious incense. This wasn’t a hippy store of the same time period, it was old-school apothecary stuffed to the gills with enchantment. I figured I was one lucky son of a gun.

12

Within this beautiful book room, much of it naturally lit by the broad store-front windows, I discovered all sorts of books, each placed ingeniously with the same earthen instinct by the woman from the herb room. Books were also herbs. So books on farm stock were nearby astrology which was kissing cousin to thick tomes of astronomy beside fiction by Borges and Kawabata and between the ficciones would be found, like specially placed leaves, these slender books of poetry. Dozens and dozens and dozens, never close by with one another, and as if placed by the shaman from the other room. It took me years to find them all because I early on discovered I was in a temple of sorts, nothing precious mind you, the floor was smooth concrete covered with brought-in snow and mud and sometimes scattered rugs, but the place and its aura asked that I work on its terms. So I did.

13

The unique books of poetry often, but not always handmade, handstitched and many of the best to my eye, came from small presses in the American west, or small town Iowa, Kentucky or someplace in New England. Even Japan. The names behind the presses were Clifford Burke, Hayden Carruth, Coleman Carroll, Jonathan Greene, James Cooney, James Koller, Ian Hamilton Finlay and Cid Corman. These books were so special to me I wouldn’t even look into them much while in the store — one glance and I knew they were gems. I’d save up and purchase three or four on every visit and then hike them back to my cabin in the woods and worship with them there.

Bill Porter (Red Pine), Bob and Susan Arnold

2009 photo courtesy Bob Arnold

14

Eventually seeking out each of the men mentioned above and with most becoming friends. It was then I learned Cid Corman, over one spell of his long publishing career, had his books printed and published in India by monks, or some zealots, quick and cheap but elegantly on rice paper, and all the monks asked was that Cid bring them no writing with foul language.

15

In San Francisco Clifford Burke was handsetting delicious books by Lew Welch and others from a wild and wooly coast which I had already been steeped into by all the western lumber I unloaded as a boy in the family lumber business. To this day I can still remember reading early Robert Sund in a boxcar we were unloading. These poets in the west looked to the far east and I was gone gone gone. But I already had been there in a long adolescent period of studying judo and eastern philosophy, which as far as I was concerned was all one when concentrating on the martial arts. By nineteen years of age lumber, judo, Japan, woods life, herbs-to-books and poetry, handmade, on-foot, were all one lifestyle constitution. And nothing in the least has changed in forty years.

16

If anything it has been enriched — by meeting Susan from the west, and by then I was so granular in my readings from the far east and west she thought I was from somewhere “out there” — and the new poets and publishers and hand printers that took up from all the names mentioned above.

17

Today Jerry Reddan at Tangram, or Greg Joly at Bull Thistle are like Clifford Burke. So are many and younger letterpresses working in Texas, Chicago or Massachusetts — too many to name, they just keep churning out and modestly appearing. Overseas wonders like Laurie & Thomas A Clark, Erica Van Horn & Simon Cutts each with their presses in their homes and in their daily lives. I must have a thing for couples because I think of Hanne Bramness and Lars Amund Vaage translating and publishing my work in Norway. Gerard Bellaart from Cold Turkey Press and his companion Siobhan Tucker keeping a deep tradition European flavor always coming my way. Gerry and Lorry Hausman, once of The Bookstore Press in my birthplace of the Berkshires, editing and publishing matchless children’s books and poetry. Gerry Loose printing poems on plant labels and distributing these world wide like johnny appleseed all comes from the highland bluffs of Ian Hamilton Finlay, as does Julie Johnston; or Franco Beltrametti and his tiny poem tribute publication Mini, a nice cross blend look and appeal ala Finlay and Corman. Same with John Martone’s tel-let in Illinois.

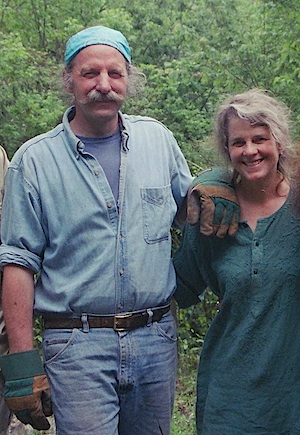

Janine Pommy Vega and Bob Arnold, 1989,

photo Susan Arnold

18

And Tom Clark (and Angelica) masterfully working his “Beyond the Pale” blog in Berkeley — and this after almost 50 years of writing, publishing and throwing support in all other venues. Or how the painter-poet Alan Lau each Chinese new year gives small paintings like poems to friends through the mail. I have one wall upstairs in my house with tiny frames of these.

19

Or how a poet like Janine Pommy Vega, who has no press but lots of punch to her, and for decades has gone into prisons or migrant camps or abused-woman hostels and worked up their poetry and stories and with whatever money she can find make these anthologies and books and booklets. The revolution must be human, my friend Walter Lowenfels used to say, and poetry can be found anywhere. The best poems have a handmade feel and smell of medicine.

20

KJ: Speaking of the hand-made feel and the cranky doctor’s office, you’d mentioned Cid Corman, one of the major figures, despite his relative obscurity, in the history of 20th century American poetry. You are his literary executor. And it turns out that Corman entrusted you with the final editorship of Origin, his centripetal journal (U.S. poetry over the last sixty years, or so, can’t be well understood without account of Corman’s magazine and his promotion of now-central figures who appeared therein), which you continued in online form, up until a couple years back. I’d like you to talk a bit about Cid Corman, how your relationship with him came to be and develop, what it has meant to you and your own poetry.

21

BA: As a boy I was always close to older folks, my elders. I respected my mother and father and still do, even though my father is dead. The two elder sisters who lived next to us in my childhood neighborhood were my friends. I’d visit their porch and rocking chairs in the evening at age seven or eight and listen to their stories. Looked into all their grayness. They listened to me, cooed like pigeons and smiled. I never lost that attachment to elders.

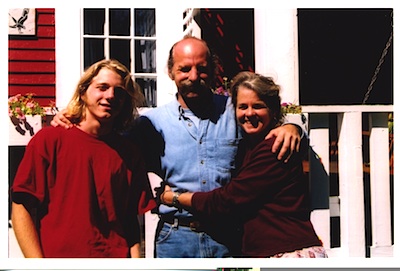

Carson, Bob and Susan Arnold at home 2002 photo J. Phillips

22

In high school I had deeper and more enduring relationships with some of my teachers than with the students. It was much the same when I graduated from high school and worked a year in the lumberyard and drew close with the carpenters; just the same when I moved the next year to Vermont and sided up with a hillbilly in the woods jack-of-all-trades. I never found the sweet old farmer at the end of the road teaching me all the simple acts; I met the losers, with a twinkle in their eyes.

23

So enters Cid . It’s 1974, the same year I met Susan. A very good year. I just might not die or freeze to death living the way I was. I had been reading Cid since high school when I discovered his name mentioned (no poems included), in Kelly & Leary’s A Controversy of Poets, still a great anthology. I’ll never forget how I was taken by Ed Dorn and his short lived magazine called Wild Dog, and then Cid’s Origin. In the backwater New Hampshire prep school town I was in, I even found a bookshop with a wizardry proprieter who stocked Ramparts and Jim Koller’s Coyote’s Journal. I read it all like a man afire.

24

I was already working for the school literary magazine and also publishing an underground paper I called RAW (“war” backwards) and my only co-conspirator and contributor was a black English teacher, fresh out of Bowdoin, and gay, striking, who’d last one year at the school. He at least lasted long enough to get me out of high school. Then we toured New England one weekend in his red mustang he christened “Diana” (Ross), which probably terrified yet fascinated my parents, and the all-white neighborhood, when he arrived and whisked me away with all the flair of Sidney Poitier.

25

Actually Jon was also there to be a witness at my draft board as I worked to earn my C.O. Status. It was 1971, the killing fields of Nixon. When I was sent to Vermont (my choice), I was hired up by a nursery school and an Episcopal Church. The nursery school teacher had been delivered by William Carlos Williams so was partial to poets; the minister was a Thomas Merton man — my lucky day. His office also had a mimeograph machine, and in 1971 I started Longhouse, by first publishing the minister’s poetry, because one should be kind to one’s landlord, and then preceding to write the poets I had been reading: Hayden Carruth, Ted Enslin, John Clellon Holmes, John Brandi, Carol Berge, Stuart Perkoff, Rosmarie Walrop, James Koller, Jack Hirschman, Janine Pommy Vega, Cid Corman. They all answered.

26

Cid wrote back from Boston or Kyoto, I can’t remember, because he was in between both cities during that time. The first part of the correspondence came as postcards, stacks and stacks, sympathetic enough but also a cool customer, and easy to chide and preach. You took your life into your hands with Cid, and if you were patient, and stayed your own person, it all paid off. By 1980 we were sailing, and that was after six years of correspondence and never having met, and when we did meet, he was flabbergasted we weren’t the same age!

27

For the next twenty years we (Susan and Bob) started to work an informal relationship of publishing Cid’s poetry and translations, plus some of the poets he brought to us as publishers. We never sketched out a plan, it was just happening. All trust. Marvelous. The postcards were gone, and the letters were long, up to three or four per week, blue aerogrammes. All during this time, Cid attempted to re-gear his Origin into some backer’s hands. He always had some generous benefactor or like-minded and much wealthier dreamer to help him hatch his schemes. The University of Maine at Orono was there for a short spell and some issues of Origin, while others pecked at the idea, but times were changing, and Cid had burned many bridges with his past life and relations. He did best with the young and eager, or else the classical ancient scholars and such he found all over the world. Famous poets drove him nuts, of course, since fame eluded him. And some of those famous forgot about him or scorned him. It’s a messy business.

Bob Arnold in the woodlot, 2009 photo Susan Arnold

28

After working almost three decades with Cid and publishing all sorts of Longhouse publications on my own with Susan, we all got through the turn of the century. Around this time Cid met a young American teaching in Japan with two adorable boys and a Japanese wife, and this was Chuck Sandy. With Chuck’s university connections and Cid’s eternal Origin dream, he was hoping to re-launch Origin with Chuck, and they wanted my work as the feature for the first issue. A preliminary sketch was drawn up for the first four issues and feature poets. In between this brainstorm, Cid came to America for the last time to take part in the centenary festival for Lorine Niedecker in Wisconsin, her home state. Cid was Lorine’s literary executor, and I would be his (and it turns out Lorine’s), so he wanted me there and he made it possible, including, as Cid insisted, Susan and our son Carson. And he achieved this same wish for another poet’s family, and he brought Chuck Sandy with him, and Shizumi, from Japan so I could meet Chuck. Luckily we met, because Cid was struck down and died some months later.

29

Chuck, holding the bag back home in Japan for Origin and all the love for his good friend, was devastated. He asked me for help, and more, he asked if I would take over the job of Origin. For the same love for Cid, I did. The idea was to uphold to a tee everything Cid wanted, which was merely sketchy, but at least I rounded up three of the four poets he wanted as feature poets, always the centerpiece of every Origin issue. I fought too hard and probably stupidly in my devotion to get aboard the fourth poet, then backed off, looked around, and liked what I saw in Dale Smith and Hoa Nguyen, and I was pretty sure Cid would have agreed. I had first tried Cid’s and my friend Tsering Dhompa Wangmo, but it was bad timing with Tsering traveling back home to Tibet and out of reach… so I returned to Texas and Dale and Hoa, and they said sure.

30

After that Susan and I worked every day, twelve hours a day, on corresponding, fetching, fidgeting and flagging down poets by email and regular mail and making the four issues. A usual Origin run was twenty issues over five years. We would prepare a quartet, and a coda, and we would do it in four seasons, honoring the usual Longhouse living of outdoors and weathering with the seasons. I didn’t want to go past Cid’s initial sketch of four issues, even though he only got that far because of declining health and his passing. His plan would have been for twenty issues. We’d surmount the same volume of poets and pages as twenty issues and gather it in an anthology of one year/4 seasons/1700 pages and all on-line, gratis. I know it is 1700 pages because we have a good friend who actually, on his own dime, printed each quarterly issue out for us and sent it as a gift through the mail. There’s nothing like a stork delivering a baby.

31

Cid loved my poetry, and I loved his. When I sent him a new book of my poems (and he published four of them from Origin) he would return the favor with a dozen poems he wrote right off the bat saying that was the highest “compliment”. Poetry was always his way. Not a physical man, but a man with an ample understanding of the physical. He was tender in ways only a filmmaker like Bresson would catch. And I still haven’t met anyone with his degree of patience and understanding. He would have made, in another life, a great family doctor.

32

KJ: That’s fascinating. But excuse me and wait a second: Did you say you are now Lorine Niedecker’s executor? That’s stunning news to me. Please talk about this a bit. How it happened and what it might mean, for us, as readers of her work down the road. Any surprises on the way?

33

BA: The short answer: I am carrying on the Lorine Niedecker executor work, via Cid’s commitment to her, as his literary executor. What he did as executor with Lorine, I am simply continuing on. As he wished. Jenny Penberthy had asked me about this a few years ago herself, and I told her the same. Jenny answered me this way, “Okay, I pretty much expected that you’d take over Cid’s role. Very good to know for sure. I have someone to send to you right away.” And I’ve been fielding questions and requests and tending to little ground-breakings for Lorine ever since.

34

There are many good people behind the scenes caring for Lorine — Jenny being one of the most vital with her editing of Niedecker’s collected works, and some of the correspondence, and scholarly studies. Invaluable. Cid was very supportive and worked with Jenny to move things into a wider audience. With me, Cid and I continued our garage band of Longhouse~Origin by publishing Lorine’s A Cook Book in the style and flavor of her own handmade books of poems she gifted around to friends. Plus Longhouse published her letter to Charles Reznikoff and another letter to Mary Hoard. Within every Niedecker letter is poem molecular.

35

On the horizon is Margot Peter’s biography of Lorine, yummy to think about, and we already have Cathy Cook’s film “Immortal Cupboard, In Search of Lorine Niedecker”. Ann Engelman is keeping the world abreast by newsletter and events of Lorine-glory via Friends of Lorine Niedecker. Amy Lutzke at the Dwight Foster Public Library in Lorine’s hometown of Fort Atkinson, is caring for Niedecker artifacts, as is Kori Oberle in the same town at the Hoard Historical Museum. I just released, through Kori’s guidance, paintings done by Lorine in the 1960s that I showcased on my Birdhouse blog celebrating the anniversary of Lorine’s passing (Dec 31). Down in Kentucky, Jonathan Greene at Gnomon Press is keeping in print The Granite Pail, Lorine’s selected poems as edited by Cid.

36

In the meantime, and back to Margot for a moment — just this week she sent to me all the letters (photocopy) of Lorine Niedecker to Jonathan Williams. Of course Jonathan sheltered Lorine’s side of the correspondence, but unfortunately it seems his letters to Lorine are lost. Margot is proposing we do a book together of these letters, published from Longhouse, that she would edit and annotate with Thomas Meyer. Too good to be true if we can all swing it. It might fit out to be just the companion in size and fellowship as the Niedecker cook book we published.

37

The future looks bright for Lorine Niedecker. Unlike many poets in busy America, she percolates slowly and won’t burn out.

38

KJ: I’m totally with you on that last assertion. I remember years ago, when I lived around the corner from Woodland Pattern Books (where I first learned of Niedecker, in fact), often sitting down with these gorgeous, tiny books by Corman they had there — I can’t recall now the publisher, maybe they were out of Japan. Haiku and tanka-like poems, but more formally open, playful in their line and word breaks. The compressed, gnomic lyric has enjoyed a definite uptick in popularity over the recent years: One thinks of Armantrout (and her various younger imitators), Foust, Massey, and others… But Corman was at work in the “sumi-e” poetic mode long before, and often in impressive ways that haven’t yet been properly reckoned. While you also work in longer forms — the moving sequence My Sweetest Friend jumps to mind — the shorter (sometimes ultra-short) lyric, whether presented discretely or in serial proceeding, has been the formal path you’ve predominantly followed.

39

Even in reverse, it’s worth saying, where in your new Hiking Down from a Hillside Sky, poems get flipped into “backtrack” lineation and to stunning effect, revealing poems as if a mirror were held up to the “originals,” there…

40

Well, I’m going on for too long. What I wanted to say is that I see you, Bob, as one of the master practitioners of the short poem at work in the U.S. today, and I wanted to ask if you feel yourself as extending, consciously honoring, a tradition in that regard — Corman and Niedecker, aspects of Creeley, say, would be in that lineage… But further back, too, and by hundreds of years. Am I right? I mean the tradition of laconic, resonant form, where perhaps things become more deeply said, or perceived, or intimated, through the art of leaving out, of letting be… Or maybe I’m getting the epistemology of it sort of backwards, putting it that way.

41

So to end, please talk about your poetry a bit, and feel free to take the matter in any which way you wish. Thank you for this exchange, Bob.

42

BA: And many thanks to you, Kent. You know, I’ve noticed during the interview most of my answers play nicely with my first twenty years — as if locked in a treasure chest — including when I first discovered Cid and now moving forward with Lorine Niedecker as well. The last forty years, almost, all with Susan, is one currency all the same: same love, same tools, same land, same river, same sky. Quite a toolbox. There’s no hindsight yet. Yesterday was today and tomorrow. It’s fresh. Most of the pleasure at making is not quite knowing, but discovering. What I do want to know: is Carson okay? Is Susan happy? Is the stovewood dry? Are the house sills firm? The roof solid? The tires with good rubber on the truck? Take that to the poetry and just watch!

43

So that’s what I mainly do with writing poems, and I am a real stickler about the short poem — the shorter the poem/the tougher I am, either at reading others or writing my own — because I want the poem to resonate and be as long feeling as any long poem and truly ring. I believe a lot of this has gone into my stone building, and I draw this out in my book of prose On Stone, where the builder has a simple resource: stone, and needing few tools. It’s all up to learning and knowing how to balance the stone, make it look handsome and true, and stand up of course, forever. Same with the poem. The lines built out of hardware but floating, and only tipsy to tip the reader into the next line and so continual. Is that too much to ask? I know in the sparest Paul Celan poem, he understands.

44

So the short poem is a buddy of mine, but so are many of the moderate-size poems where many of my love poems reside; and then there are the long poems, and I’ve just completed a 105 piece long poem called Yokel that took ten years to write. It’s farm narrative and portraits and outdoor work poems covering four decades of watching this old life and tradition around me disappear from the map. It just couldn’t be done with small poems only — just as Basho’s travel notebook had to be pinpoint poems compassed around a netting of anecdotes and ruminations. My long poem Yokel has big brawny pieces wide as the barn door and a river sounding endless to the ears. It takes the architecture of a long poem to carry that span.

Bob and Susan Arnold at work in Bearsville, NY. 2005 photo Janine Pommy Vega

45

As to carrying on traditions — I love it and honor it and practice it and likewise sometimes like to see it busted down and rebuilt. I’m all for revolution if builders are taking part. Back when I was young I was living a duo discipline of the manual handwork skills and poetry all at the same time, same day, same hour. Well, I still am. I’ve always had a book in my lunch pail on the jobs, and yes indeed it was often Creeley, O’Hara, Zukofsky, Patchen, Baraka, Olav Hauge, Rimbaud, Hikmet, Jaan Kaplinski, Niedecker, Snyder, Whalen, Neruda. William Carlos Williams forever and ever. Blake!

46

This was never name-dropping: these were companions in a somewhat isolated life. Very much Rexroth, his quixotic poem and Asian translations which opened dozens of windows with curtains blowing back to Li Po, Buson, Issa and most so Wang Wei for me. The latter was my only companion for early years chopping wood and for decades onward I searched up all the mountain hermits of Asia via Corman, Seaton, Hinton, Snyder, Schelling, O’Connor and Red Pine… all excellent translators and craftsman and many became friends.

47

Cid was very important as a close friend, most so how we edited and thought together, and for his translations. His own poetry was a bit too singular, although I can always pick out dozens of favorites by him. I was after more of a lust in poets, or landscape, and body with others… so I often ended up the last twenty years or so with poets in Eastern Europe, South America, or any province with those trying to last on an edge. A poet in snowy Estonia, say, could make an awful lot of sense to a poet in Vermont.

48

As essential as the poets read are the other writers and a living that build the fiber of a poet. I can’t not think of the full texts of Whitman, Thoreau, Dickinson, Pound, Rockwell Kent, the absolute of Merton, and someone like Henry Miller or Kerouac or Jaime de Angulo for daring and rhythm, or Muriel Rukeyser and Jeffers for their breadth. Precious few ever learn how to be normal and straight forward and get things picked up, and likewise allow the dream and give it room to contract and expand. It’s a tough ticket to ride. As we extrapolate as a person and a planet the act of being noticed, recognized, so fame seems to be the main incentive. It’s about the only function and way that can juxtapose the greatness of the universal.

49

So we are all living out of whack while the greater body is scientific and wishes to make sense for organs and blood stream and breathing rights and a registry of brain function. It takes nerve to make sense. And since I consider the body very much part of the earth, as do the Chinese in the body of the turtle — that earth household Gary Snyder once spoke to — I want where I walk and work and build and stay-put to have part mystery to it for the imagination, and likewise be resolute. If that’s tradition, or just getting-by, let’s have it. And by goodness, let’s learn to laugh.